Editor’s note: This essay sits within the Cultivated library on learning, creativity, and cognitive systems. It explores analogue tools as environments for thinking — and why materiality still matters in a digital world.

Paper as Thinking Infrastructure

There is something quietly powerful about a blank notebook.

In a world saturated with screens, notifications, and infinite digital possibility, paper offers something rare: bounded space, physical presence, and attention with friction.

For me, analogue tools are not nostalgic curiosities. They are cognitive environments — scaffolding and space for thinking, learning, and creating.

Tools as Environments, Not Objects

We often talk about tools as if they are neutral.

They are not.

Every tool shapes behaviour, attention, and cognition. A notebook is not just paper; it is a container for thought. A pen is not just ink; it is a physical interface between mind and world.

Digital tools are optimised for speed, scale, and connectivity.

Analogue tools are optimised for presence, reflection, and thinking.

They slow thinking down just enough for meaning to emerge.

The Friction That Creates Thought

Friction is often framed as inefficiency.

In thinking, friction is essential. Because on the other side there is reward.

Writing by hand introduces pauses. Turning pages introduces rhythm. Crossing out words introduces reflection. The material constraints of paper force prioritisation and intentionality.

On a blank page, there is no algorithm, no infinite scroll, no dopamine loop.

There is only you, attention, and the mark you choose to make.

That friction is not a bug.

It is cognitive architecture.

It leads to reward.

Embodied Cognition and the Hand

When we write, sketch, or map ideas physically, the body participates in thinking.

The movement of the hand, the feel of the paper, the resistance of the pen — these are not incidental. They anchor thought in the body, making ideas felt as well as understood.

This is why handwriting aids memory, why sketching unlocks insight, and why diagrams clarify complexity.

Analogue tools externalise thinking into the world, turning cognition into something visible, spatial, and manipulable.

Ritual, Meaning, and Creative Attention

Analogue practices also create ritual.

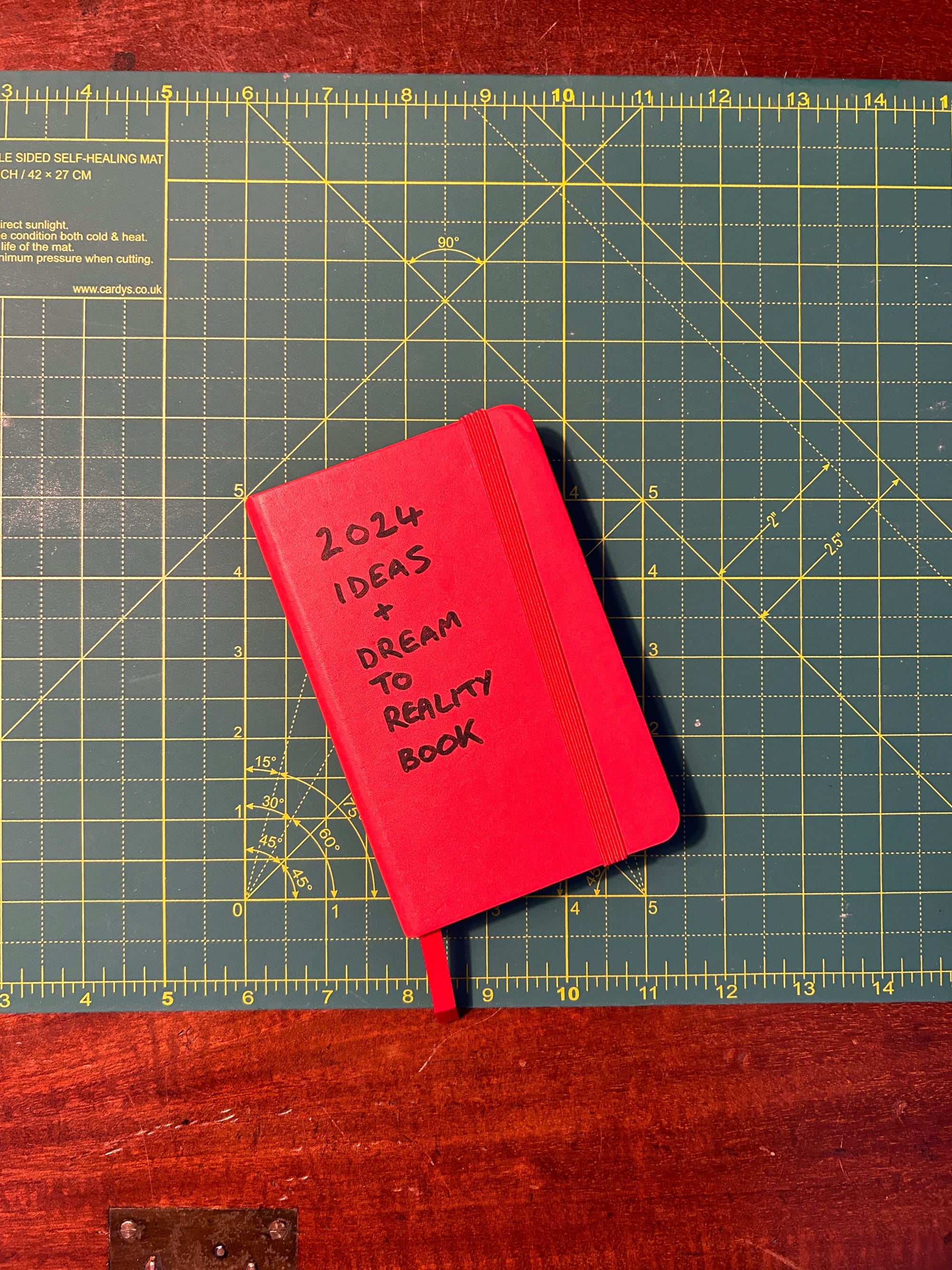

A dedicated notebook for ideas.

A journal for reflection.

A sketchbook for exploration.

These are not productivity hacks.

They are ritualised spaces for different modes of being.

By assigning material containers to mental modes, we create environmental affordances:

When I am here, I think like this.

This is not organisation.

It is identity design through tools.

Digital and Analogue Are Not Opposites

This is not an argument against digital tools.

Digital systems are extraordinary for collaboration, storage, synthesis, search and distribution.

Analogue tools are extraordinary for generation, sensemaking, and presence.

The most effective knowledge systems weave both:

- Analogue for thinking

- Digital for organising and amplifying

One is cultivating. The other is infrastructure.

Why This Still Matters

In organisations, we obsess over software, dashboards, and workflows.

In creativity, we obsess over apps, platforms, and productivity systems.

But thinking still begins somewhere quieter:

with a question, a sketch, a note, a margin scribble.

Paper is not obsolete.

It is thinking technology that has survived every technological revolution because it serves a fundamental human need: to think in the world, not just in the head and capture those thoughts.

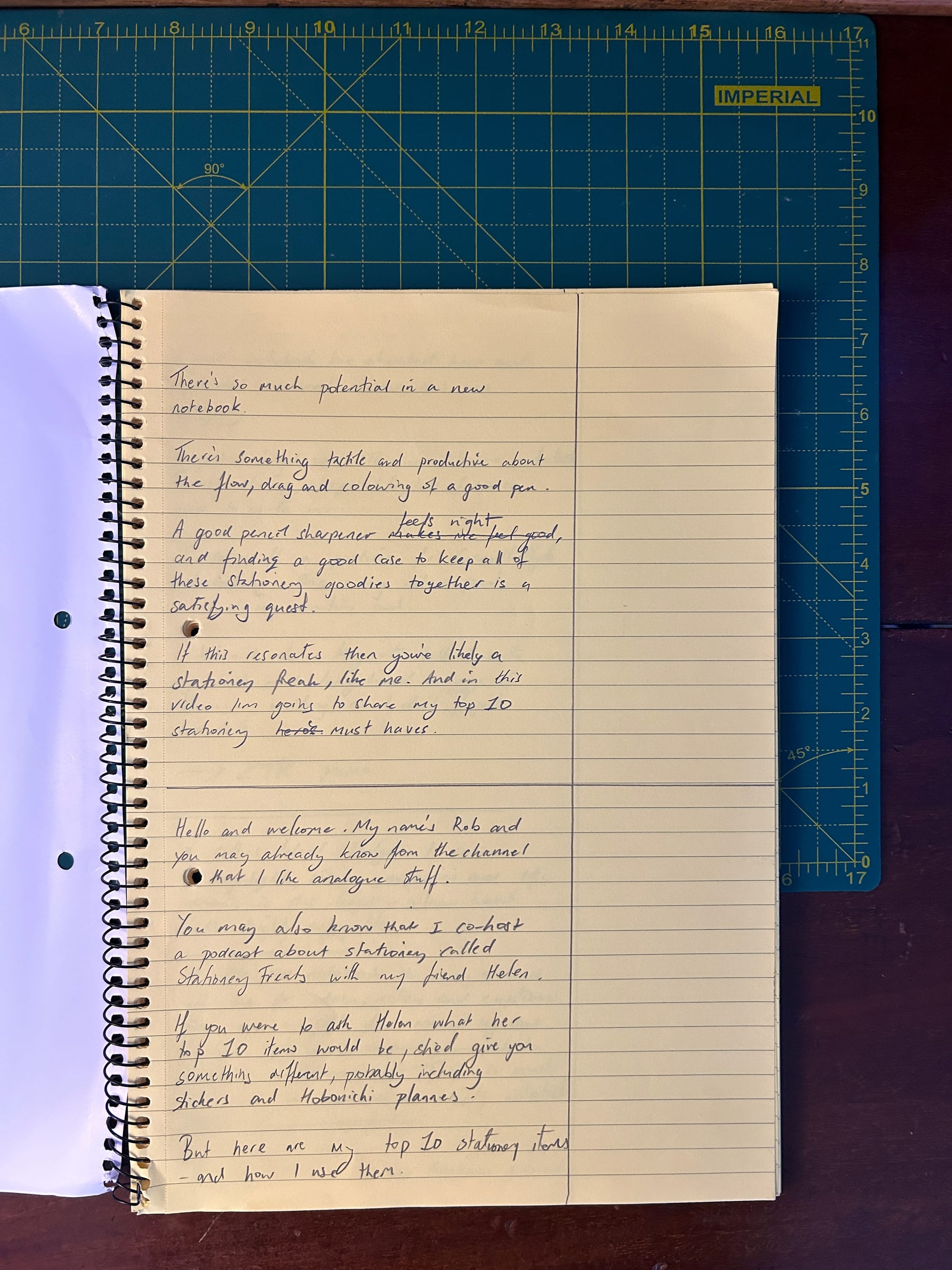

A Personal Practice

My own analogue practices are simple: notebooks for ideas, journals for reflection, sketchbooks for exploration. These are not productivity systems; they are thinking spaces and climates.

They create space for ambiguity, curiosity, and slow cognition.

They remind me that thinking is not just processing — it is a tactile, embodied act.

The Bigger Picture

Analogue tools are not about nostalgia.

They are about attention, embodiment, and meaning in a digital age.

They slow us down just enough to notice what matters.

They externalise thought so it can be shaped.

They create rituals that make creativity and learning sustainable.

In a world optimised for speed, paper remains a quiet technology for depth.

Video

Editor’s note: This essay grows from an earlier exploration in another medium. The thinking remains central, even as the format has changed.

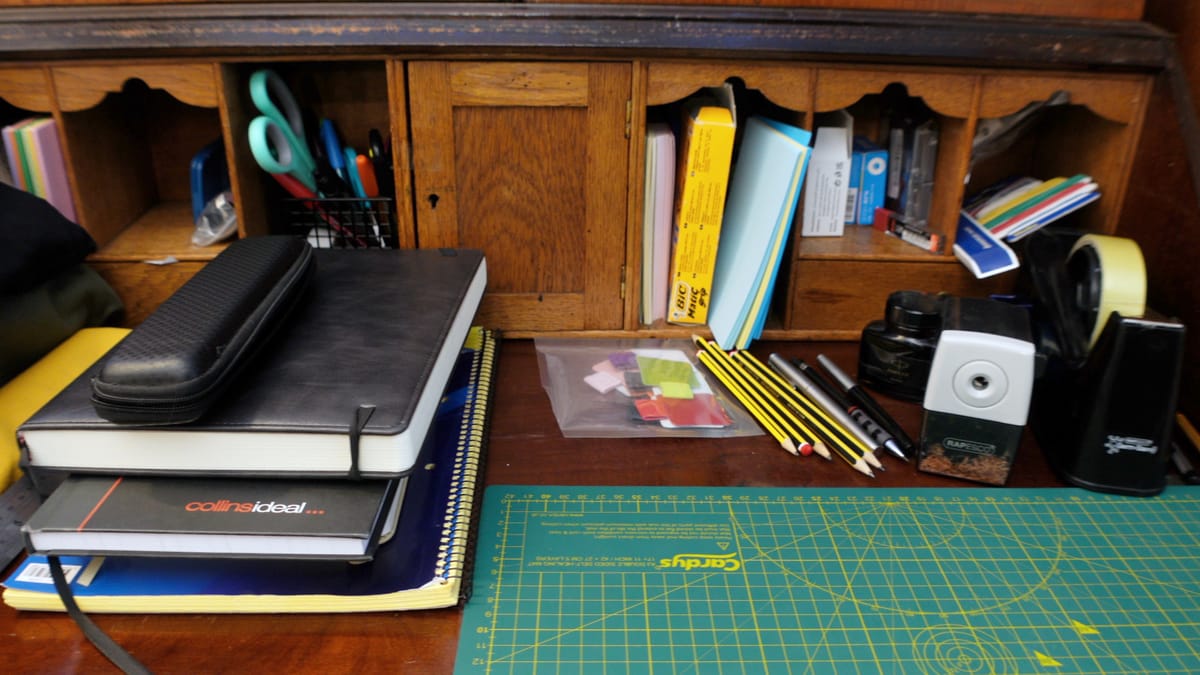

Some of my Stationery

Some snaps of my stationery

This piece forms part of Cultivated’s wider body of work on how ideas become valuable, and how better work is built.

To explore further:

→ Library — a curated collection of long-form essays

→ Ideas — developing thoughts and shorter writing

→ Learn — practical guides and tools from across the work

→ Work with us — thoughtful partnership for teams and organisations