Editor's Note: This essay is part of the Cultivated canon — a body of work exploring learning as a practical craft. It sits alongside other pieces on note-taking, attention, and sense-making, and reflects a recurring theme in this library: that how we structure information shapes how we think.

Why the Cornell Note-Taking Method Still Works

I discovered the Cornell Note-Taking Method over a decade ago — and promptly ignored it.

It sounded dull. Academic. Slightly bureaucratic.

Not at all aligned with the dynamic, free-flowing note-taking system I believed I needed at the time.

Then, one day, I tried it properly.

I haven’t really stopped since.

What surprised me most was not how tidy the notes looked, but how much clearer my thinking became. The method didn’t just organise information — it created space for interpretation.

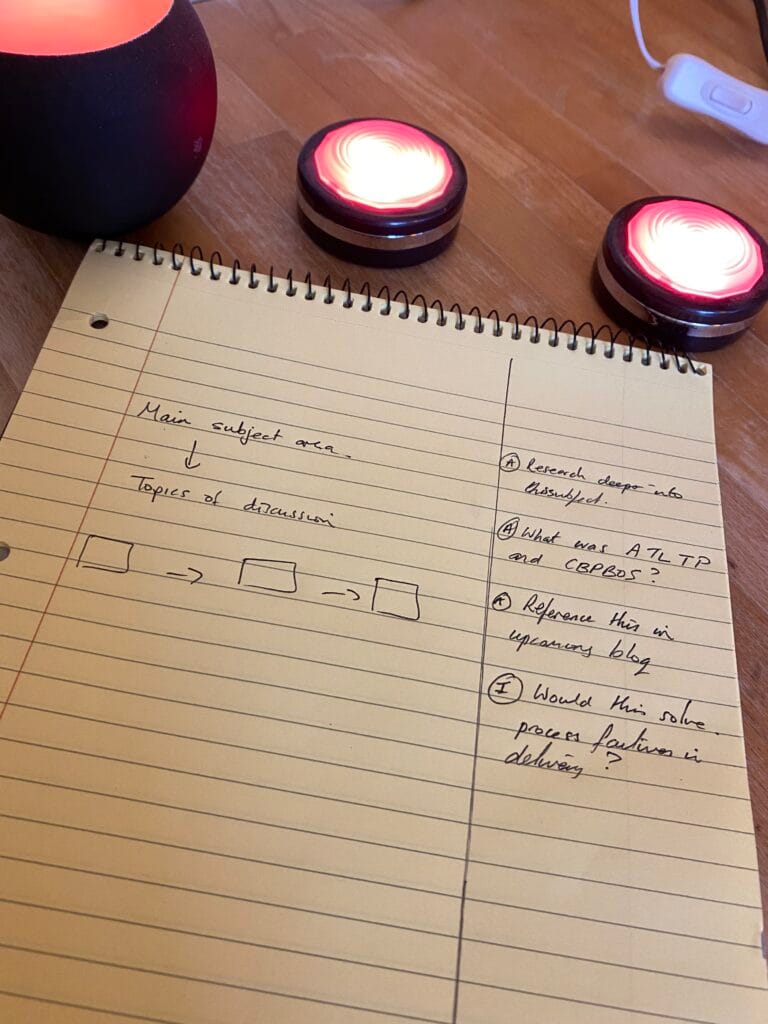

At its simplest, the Cornell method divides a page into two distinct areas.

The larger section captures what is happening: discussion, information, decisions, explanations. The narrower column is reserved for something else entirely — questions, actions, reflections, connections, and emerging ideas.

This separation is the point.

Most note-taking systems fail because they treat everything as equal. Ideas, facts, decisions, and reactions are all written in the same stream, competing for attention. Over time, meaning gets buried beneath volume.

The Cornell method introduces a deliberate asymmetry. Information lives in one place. Sense-making lives in another.

That distinction matters.

When used in meetings, the method allows the conversation to be recorded without interruption, while still giving you a place to notice what matters. Actions, tensions, questions, and moments of insight are not lost inside paragraphs of notes — they are surfaced.

When used for learning, the effect is even more pronounced. The act of deciding what belongs in the margin forces engagement. You are no longer transcribing; you are interpreting. You are choosing what deserves attention.

This is why the method endures.

It mirrors how thinking actually works. We first absorb, then we react. We listen, then we judge. We capture, then we decide what to do with what we’ve captured.

Good note-taking is not about recording everything. It is about creating a structure that allows meaning to emerge later.

I now use the Cornell method almost exclusively for meetings and learning notes. I also use it when drafting talks in long-hand, where separating structure from insight becomes even more valuable. The main body holds the narrative. The margin holds the moments that need work.

Over time, those margins become the most important part of the page.

They are where ideas form, where actions crystallise, and where understanding deepens.

The reason the Cornell method still works is not because it is clever or efficient. It works because it respects the difference between information and thought — and gives each its own space.

And in a world drowning in information, that separation is a quiet advantage.

Video

Editor’s note: This essay grows from an earlier exploration in another medium. The thinking remains central, even as the format has changed.

This piece forms part of Cultivated’s wider body of work on how ideas become valuable, and how better work is built.

To explore further:

→ Library — a curated collection of long-form essays

→ Ideas — developing thoughts and shorter writing

→ Learn — practical guides and tools from across the work

→ Work with us — thoughtful partnership for teams and organisations