Editor’s Note: This essay sits within the Cultivated canon exploring energy, attention, and creativity at work. It is not a management framework or engagement model, but a reflective lens — an invitation to notice how capable people (including ourselves) drift away from creation when systems fail to offer meaning.

From Escape to Creation

We all get some leisure time.

Maybe not much — kids, careers, and life have a habit of filling the gaps — but enough to choose how we spend our attention.

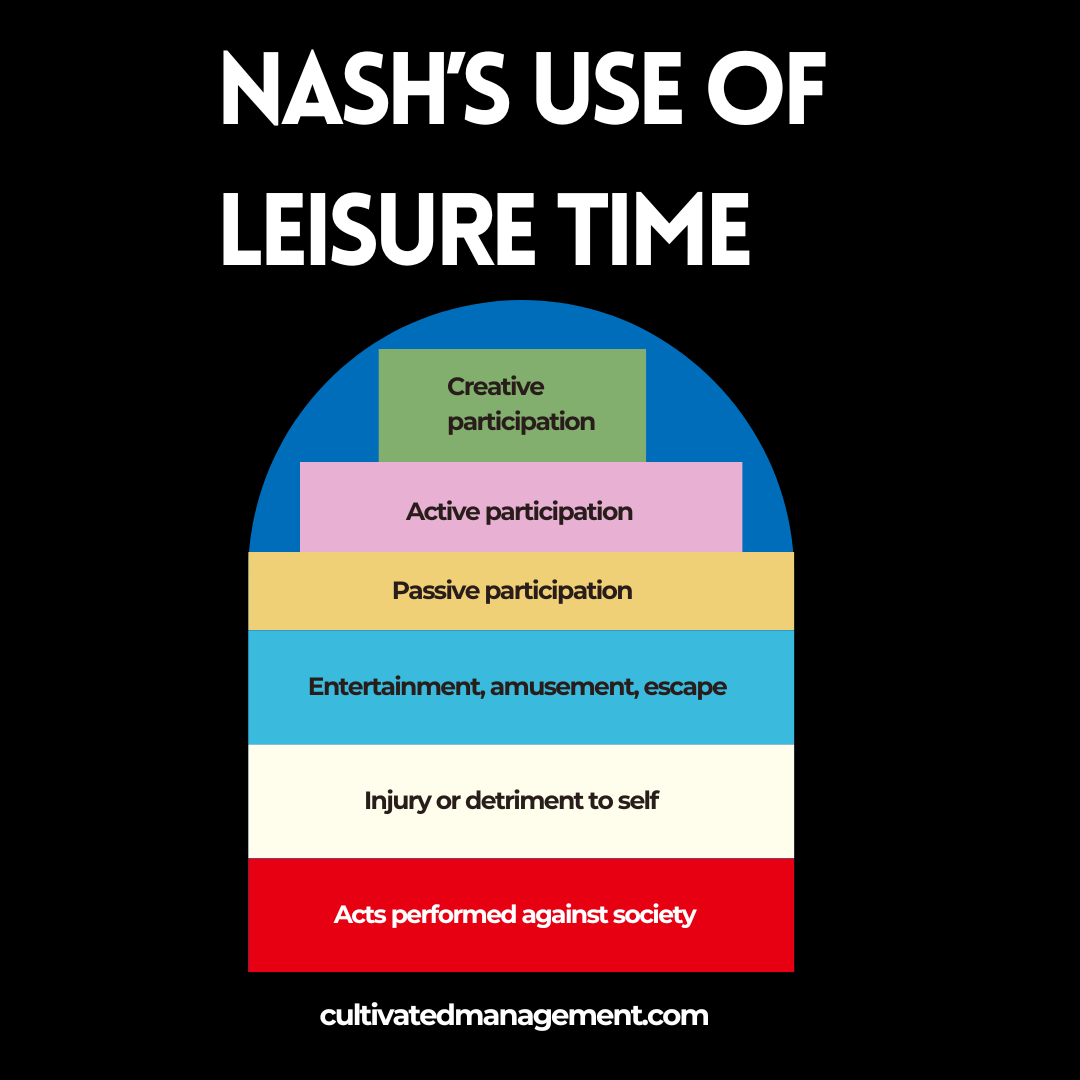

Nearly a century ago, Jay B. Nash proposed a simple model for how people use that time: the Leisure Time Pyramid.

Yes, it’s old.

Yes, it’s flawed.

Very 1920s. Light on data. Heavy on moral framing.

And yet — when I first came across it, I found myself quietly unsettled.

Because I realised something uncomfortable:

I was spending far more time in escape than I wanted to admit.

This essay can also be explored in audio form. You’re welcome to listen — or continue reading below.

A Simple Model Worth Playing With

Nash’s model imagines leisure as a loose hierarchy — not a pyramid in the strict sense, but close enough to be useful.

At the base are activities that numb, distract, or harm.

At the top are activities that create.

In plain language, the movement is simple:

from escape → toward participation → toward creation

Here’s the shape of it.

Escape

Entertainment as anaesthetic.

Scrolling. Bingeing. Killing time.

We all need escape sometimes.

The problem isn’t escape — it’s living there.

When escape becomes the default, energy dulls.

Nothing accumulates. Nothing grows.

Participation

Watching others do meaningful work.

Learning by observing. Following someone else’s script.

This can be healthy — even necessary.

But it’s still consumption.

You’re present, but not yet shaping anything of your own.

Creation

Making something that didn’t exist before.

Writing. Designing. Building. Gardening. Starting. Improving.

Creation is effortful.

It requires attention, space, and the risk of failure.

It’s also where meaning tends to live.

A Story About Netflix

Years ago, I joined a large organisation as an interim VP of software engineering.

Within the first week, I discovered something surreal.

A significant portion of the team were playing a game they called The Netflix Challenge.

The rules were simple:

Watch as much Netflix as possible during work hours — without being caught.

They had:

- a leaderboard

- a shared top-20 shows list

- time tracking

- commentary

It was disturbingly well organised.

What struck me wasn’t laziness.

It was ingenuity pointed in the wrong direction.

These were capable, intelligent people.

They weren’t avoiding work — they were escaping meaninglessness.

On Nash’s model, this sits squarely in escape.

From the organisation’s perspective, it was value leaking away.

Not through rebellion — but through boredom.

When Comfort Masquerades as Engagement

Here’s the uncomfortable part.

That same team scored well on the company’s engagement survey.

Why?

They were comfortable.

Low pressure. Low expectation. Plenty of time. Plenty of Netflix.

Why rock the boat?

Which is why I’ve never trusted engagement scores on their own.

Comfort is not contribution.

Happiness is not value.

And disengagement is often a system signal — not a personal failing.

What This Lens Reveals

When you look through Nash’s model — lightly, without moral judgement — a pattern emerges.

Most people don’t want to escape their work.

They drift there when creation feels inaccessible.

Not because they lack talent.

But because clarity is missing.

Because the system is noisy.

Because effort no longer connects to outcome.

Escape becomes the least costly option.

Moving, Gently, Upward

The point isn’t to shame escape.

It’s to notice it.

To ask:

- Where is my attention actually going?

- Where is my team’s energy being spent?

- What conditions make creation feel possible — or impossible?

Most people want to make things.

They want to improve something.

They want to grow.

When they can’t, they escape instead.

A Quiet Question

Nash’s model isn’t scientific truth.

It’s a prompt.

A way of asking better questions about how we spend the one thing we never get back: attention.

Less escape.

More participation.

And when possible — creation.

Because whether in life or work, meaning rarely appears by accident.

It emerges when people are given space to make something that matters.

This piece forms part of Cultivated’s wider body of work on how ideas become valuable, and how better work is built.

To explore further:

→ Library — a curated collection of long-form essays

→ Ideas — developing thoughts and shorter writing

→ Learn — practical guides and tools from across the work

→ Work with us — thoughtful partnership for teams and organisations