Editor’s Note: This piece sits within the Cultivated canon on learning, systems, and the journey from idea to value. Training does not change organisations. Behaviour does.

Learning Is Behaviour Change

We spend enormous time talking about learning. Courses, workshops, frameworks, certifications. Entire industries exist to package knowledge into consumable units.

And yet, most training does not change anything.

Learning only matters when behaviour changes on organisations.

If behaviour does not shift, little has been learned

— regardless of hours logged or certificates issued.

Organisations measure the wrong things.

They track attendance, completion rates, and engagement scores. These metrics are tidy, reportable, and largely meaningless.

The only meaningful question is: Did people behave differently?

Learning as a System, Not an Event

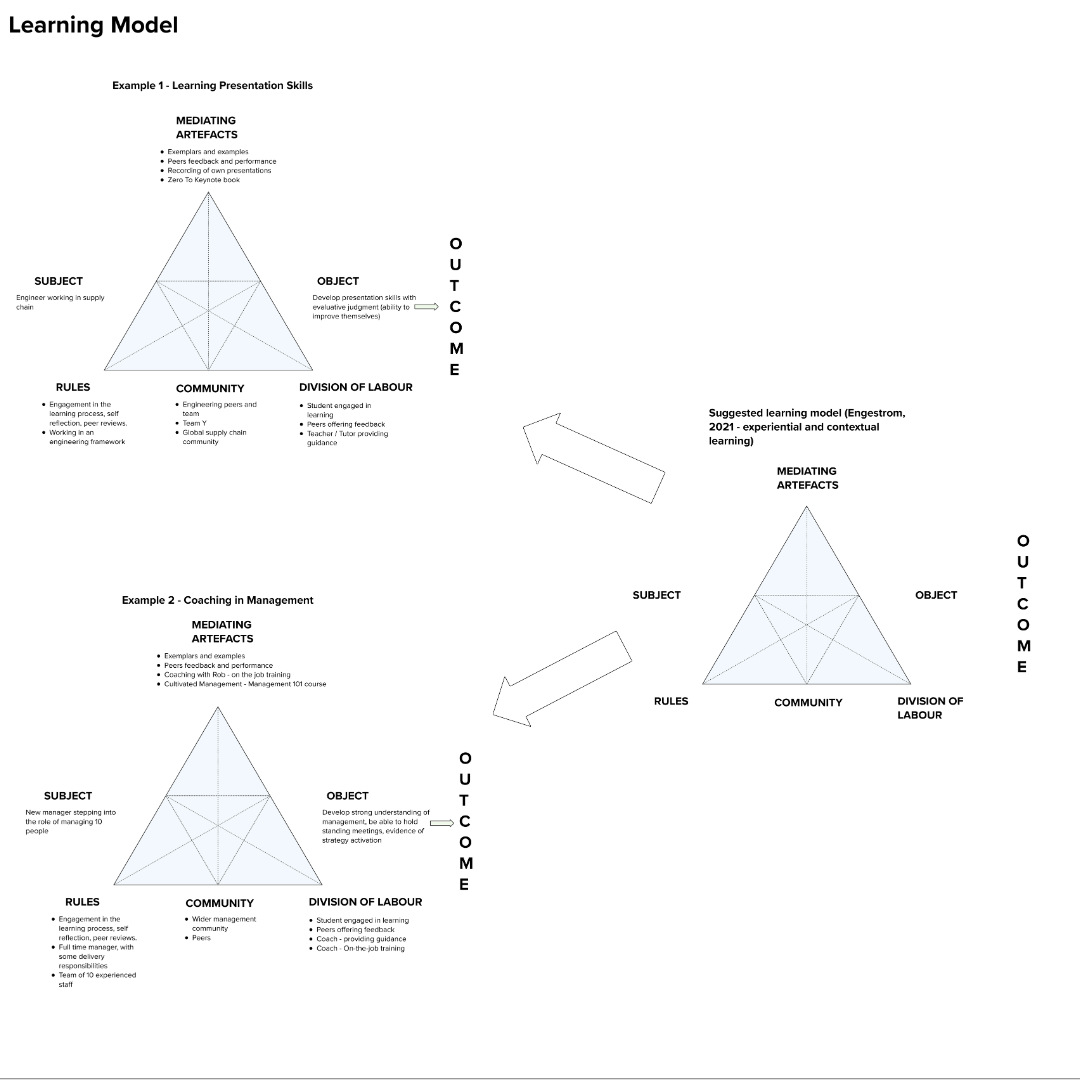

One useful lens for understanding learning is Yrjö Engeström’s Activity Theory.

In academic form, it is complex.

In practice, it offers a simple insight:

Learning does not happen in isolation. It happens in systems.

People do not learn in classrooms. They learn in contexts — shaped by rules, tools, communities, expectations, incentives, other people and power structures.

A training session is a moment.

Behaviour change is a system outcome.

The Cultivated View: From Knowing to Doing

Most organisations treat learning as a content delivery problem.

In reality, learning is a design problem: designing the climate in which new behaviour becomes the easiest path.

A first-time manager does not become a manager by attending a course.

They become a manager through feedback loops, modelling, coaching, expectations, consequences, and practice.

Courses supply language.

Systems supply behaviour.

Why Training Fails

Training fails when it ignores the system around the learner.

- Rules contradict the learning (e.g., “be reflective” in a culture that punishes mistakes).

- Communities resist change (peers reinforce old habits).

- Tools do not support new behaviours (no time, no templates, no feedback loops).

- Roles are unclear (nobody owns development).

- Outcomes are undefined (what does “better” actually mean?).

In these conditions, training becomes theatre.

Learning as Behavioural Infrastructure

Effective learning environments are behavioural infrastructures. They make new behaviours visible, supported, rewarded, and normal.

This might include:

- Exemplars and role models

- Coaching and shadowing

- Peer feedback

- Structured practice

- Reflection and evaluation

- Clear expectations of “what good looks like”

The point is not content.

The point is conditions and climate.

Evaluative Judgement: The Endgame

The highest form of learning is not skill acquisition. It is evaluative judgement — the ability to observe oneself, assess performance, and self-correct.

This is when learning becomes self-sustaining.

No trainer required.

Just continuous refinement.

Organisations that cultivate evaluative judgement scale learning without scaling training.

The Takeaway

Training is an input.

Behaviour is the output.

Systems determine whether the output changes.

If you want learning to stick, stop asking how many courses people completed.

Start asking how work is done differently.

Learning is not content consumed.

It is behaviour cultivated.

Bibliography

[1] A. Blunden, ‘Engeström’s Activity Theory and Social Theory’.