Capable vs. Capability: How to Build High-Performing Individuals, Not Just Teams

Discover the critical difference between capable and capability, and learn how to develop individuals who can deliver real business results. Practical strategies, examples, and coaching tips for managers and leaders.

Capable vs. Capability: Building People, Not Just Teams

Managers and leaders often ask me about growing capabilities, scaling capabilities, deploying capabilities, and sustaining capabilities. They want advice on building a competent team.

Before diving into solutions, it helps to break down the word capability and ensure we’re deploying the right initiatives to achieve our ultimate goal: to have people capable of delivering value to customers and the organisation now, and in the future—while enriching the workplace along the way.

Too often, the word “capability” is used loosely. Some use it to describe services offered, some to describe skills or competencies, and some as a catch-all term for what a team can do. This conflation causes real problems.

In this post, I’ll clarify the difference between capable and capability, and offer strategies for growing your team’s ability to get the job done—at an individual level.

Seeing People Grow (and Leave)

There are few experiences more rewarding than seeing people develop under your leadership. As they grow in their ability to do current and future work, they become more employable, more experienced, and more capable of adding value.

It’s a paradox: the best managers build teams that others will want to hire from. People leaving isn’t a failure—it’s a sign you’ve done your job well. But to achieve this, you need to focus on individuals, not abstract notions of “team capability.”

Capable vs. Capability

The most important distinction:

- Capable – someone can already do the work.

- Capability – someone has the potential to become capable.

Originating in the 1500s, “capability” means “the quality of becoming capable, the ability to receive or power to do, an undeveloped faculty or property.” In other words, capability is potential, not current competence.

This distinction is subtle but crucial. Most managers conflate these terms, leading to poor decisions around training, delegation, and service delivery.

Example:

- Bob is a very capable marketing manager.

- Nish has the capability to become a very capable marketing manager.

Misunderstanding this difference can have serious consequences, as we’ll see next.

When Capability Is Overstated

I worked with a consultancy where the leader told her sales team, “We have the capability to create amazing strategies for clients.”

Reality check: only one person on the 50-person team was actually capable. Five others had the capability to become capable over time, with training from that one expert.

Result? The sales team sold the service as if the entire team could deliver. The single capable expert became overloaded. Some team members struggled, one went on long-term sick leave, and the business lost money and goodwill.

Lesson: Be precise. Know who is capable, who has capability, and who lacks either. Build learning programs that turn potential into performance.

Focus on Individuals, Not Teams

You don’t manage a team; you manage individuals.

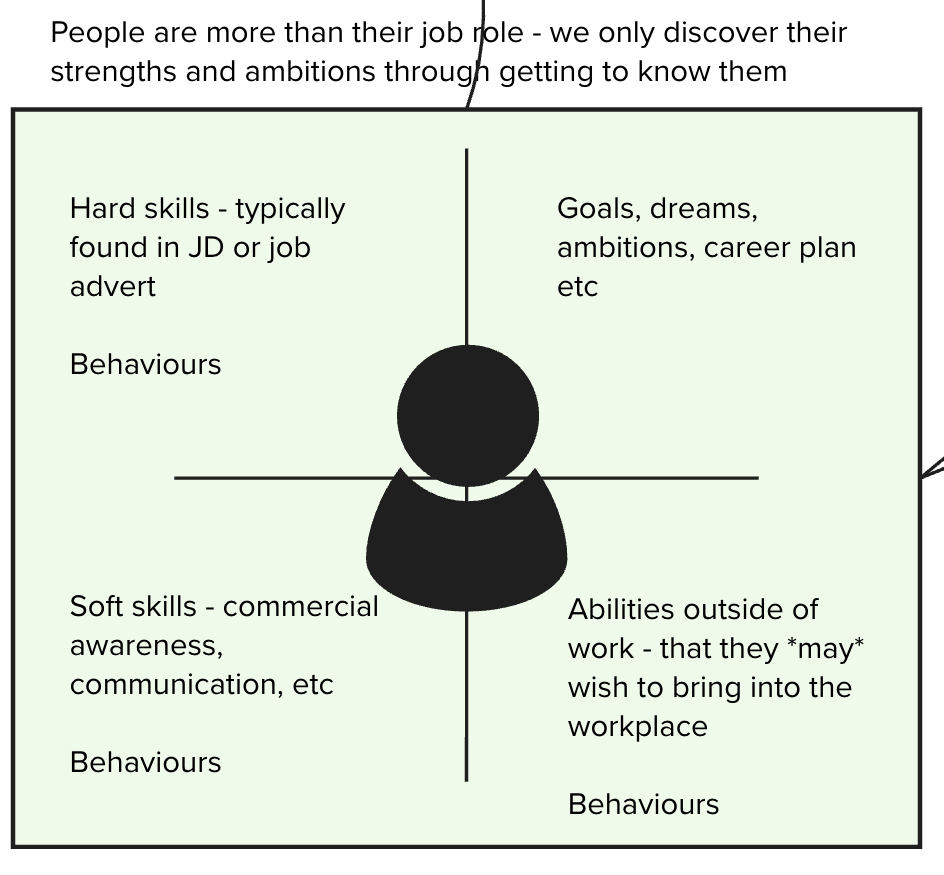

Teams are collective nouns, abstractions. Individuals have unique abilities, motivations, career goals, and potentials. Effective managers:

- Know who is capable.

- Identify who has the capability to grow.

- Recognize who will never be able—or willing—to take on certain roles.

Training and coaching should target individuals, not teams. A one-size-fits-all course or generic HR program rarely develops real competence.

Learning by Example: The Flute

Imagine learning to play the flute.

- I’m not capable right now.

- I have the capability—I play other instruments, so I can learn.

- I need goals, standards, and practice.

A structured learning plan involves:

- Setting goals and standards (e.g., play “Fur Elise” at a party in 3 months).

- Learning through information and practice.

- Mentorship from someone already capable.

- Measuring progress against standards.

This mirrors business: develop capability into capable through structured, individual-focused coaching and on-the-job training.

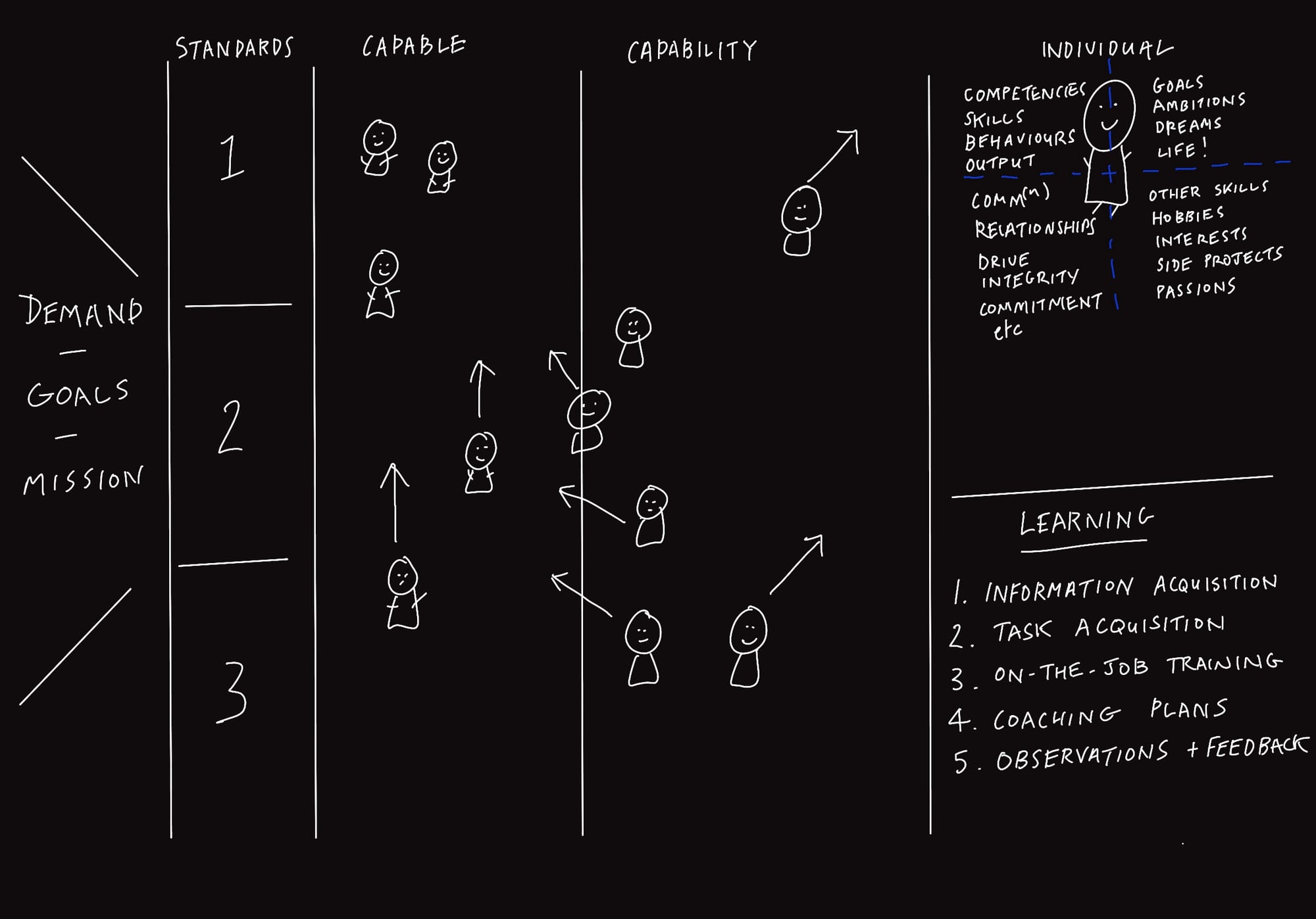

A Framework for Growing Capability

- Goals and Strategy: Define what work needs to be done now and in the future. Align training to business needs.

- Set Standards: Define behavioural standards, not just skills. Who should be capable at what level?

- Get to Know Individuals: Understand motivations, strengths, weaknesses, and aspirations. 1:1 conversations are essential.

- Face Reality: Identify who is capable, who has capability, and who does not.

- Set Coaching Plans: Create individualised learning plans to turn capability into capable. Include timelines, resources, and mentors.

- On-the-Job Training: Learning is most effective when paired with someone already capable. Task acquisition beats theory alone.

- Measure Progress: Assess behavioural change, business results, and individual growth—not just course completion or attendance.

Key Takeaways

- Distinguish capable (can do now) from capability (potential to do).

- Focus on individuals, not teams.

- Identify who can do the work, who could grow into it, and who shouldn’t be assigned it.

- Align learning and coaching to both the business and the individual.

- Use real work, mentoring, and behavioural standards to develop real competence.

- Recognise that every individual has more to offer than their job description.

Effective management isn’t about building a team with capabilities; it’s about cultivating capable individuals whose strengths, abilities, and passions are aligned to the business.