Friction and Reward

Two forces shape almost everything in an organisation: the friction that slows people down, and the rewards that make effort feel worth it. Reduce one, strengthen the other — and work starts to move.

Editorial Note: This is a cornerstone concept in the Cultivated canon — a simple lens that sits beneath a lot of what we publish about clarity, systems, and value. When “friction” and "reward" appears across the library, this is the home base: two forces that explain why work stalls, why customers leave, and why good people quietly stop trying.

Friction and Reward

Business improvement doesn’t need to be mystical.

Beneath the programmes.

Beneath the jargon.

Beneath the theatre of “transformation”.

Two forces keep showing up.

Friction.

And reward.

Reduce the former.

Strengthen the latter.

And things begin to move.

People move.

Customers move.

Work moves.

This essay can also be explored in audio form. You’re welcome to listen — or continue reading below.

Earlier in my career I kept reaching for the same idea, but I used different words.

Resistance and outcomes.

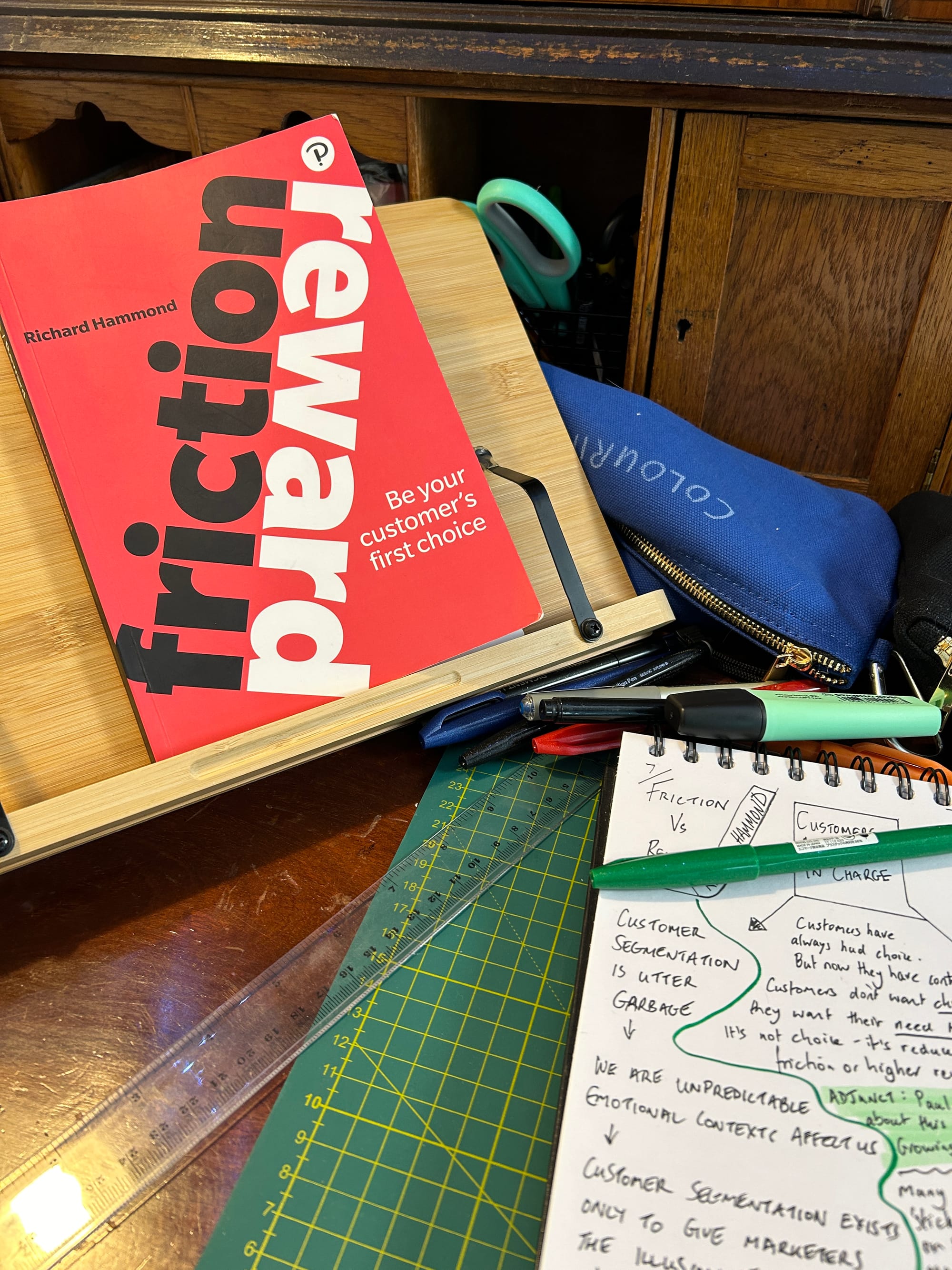

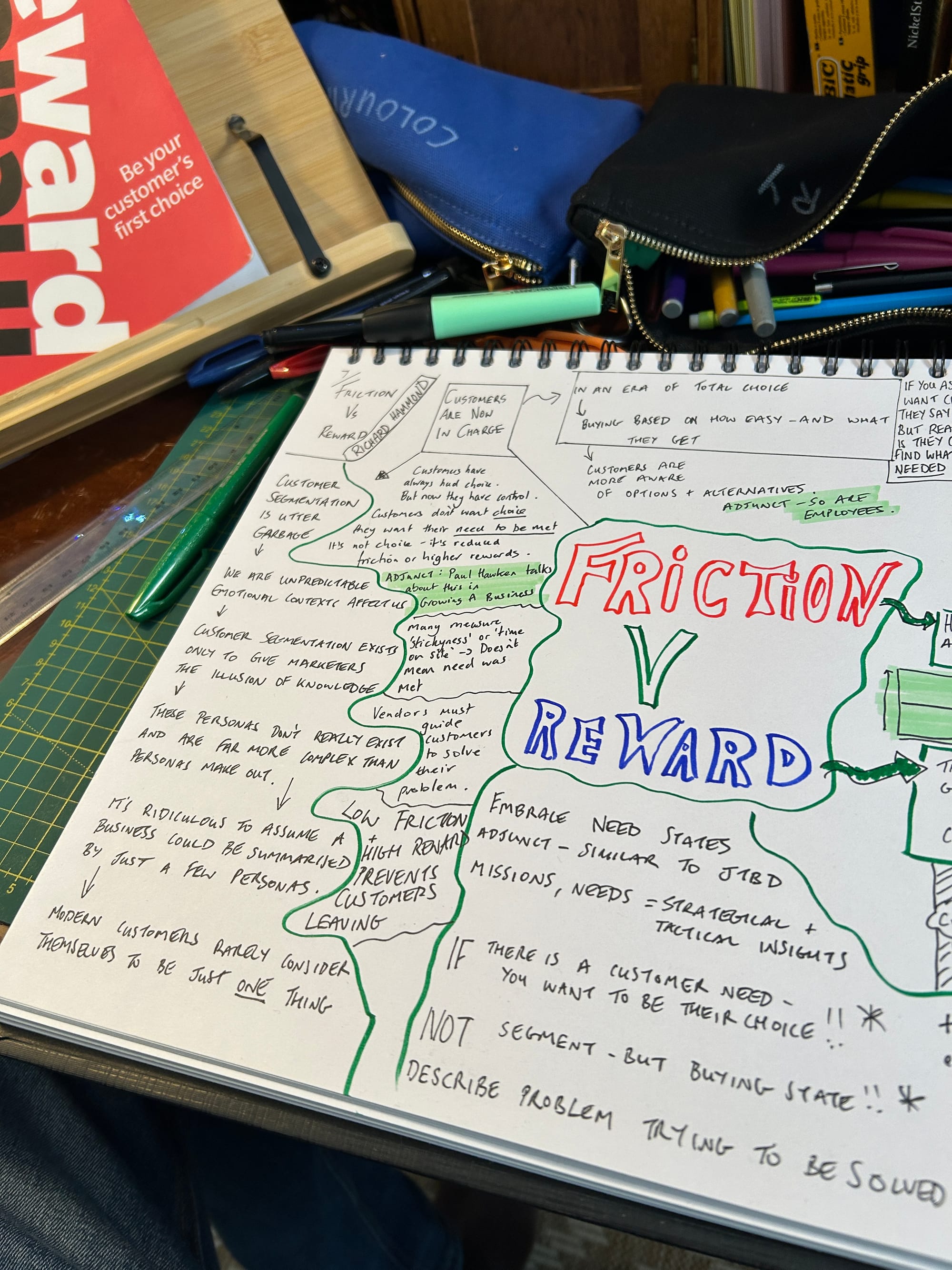

Later I found the sharper label in Richard Hammond’s work: friction and reward. (aff link)

His writing comes from retail — from queues, checkouts, delivery promises, the reality of customer choice.

But the lens travels.

It travels remarkably well.

Because organisations are full of moments where someone is trying to do something.

Buy.

Return.

Ask.

Join.

Leave.

Learn.

Ship.

Decide.

And in every one of those moments, the question is quietly the same:

How hard is it?

And what do we get on the other side?

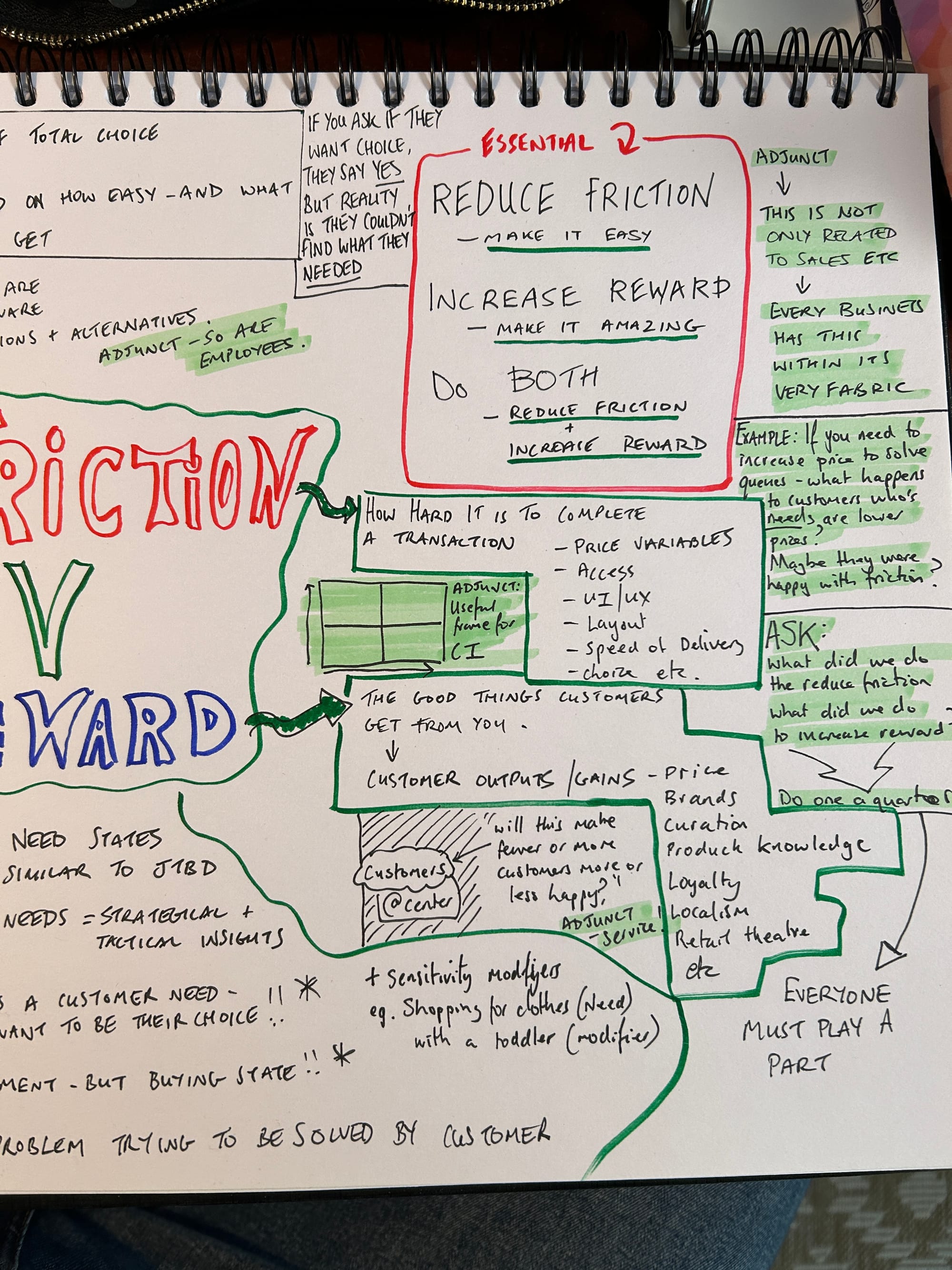

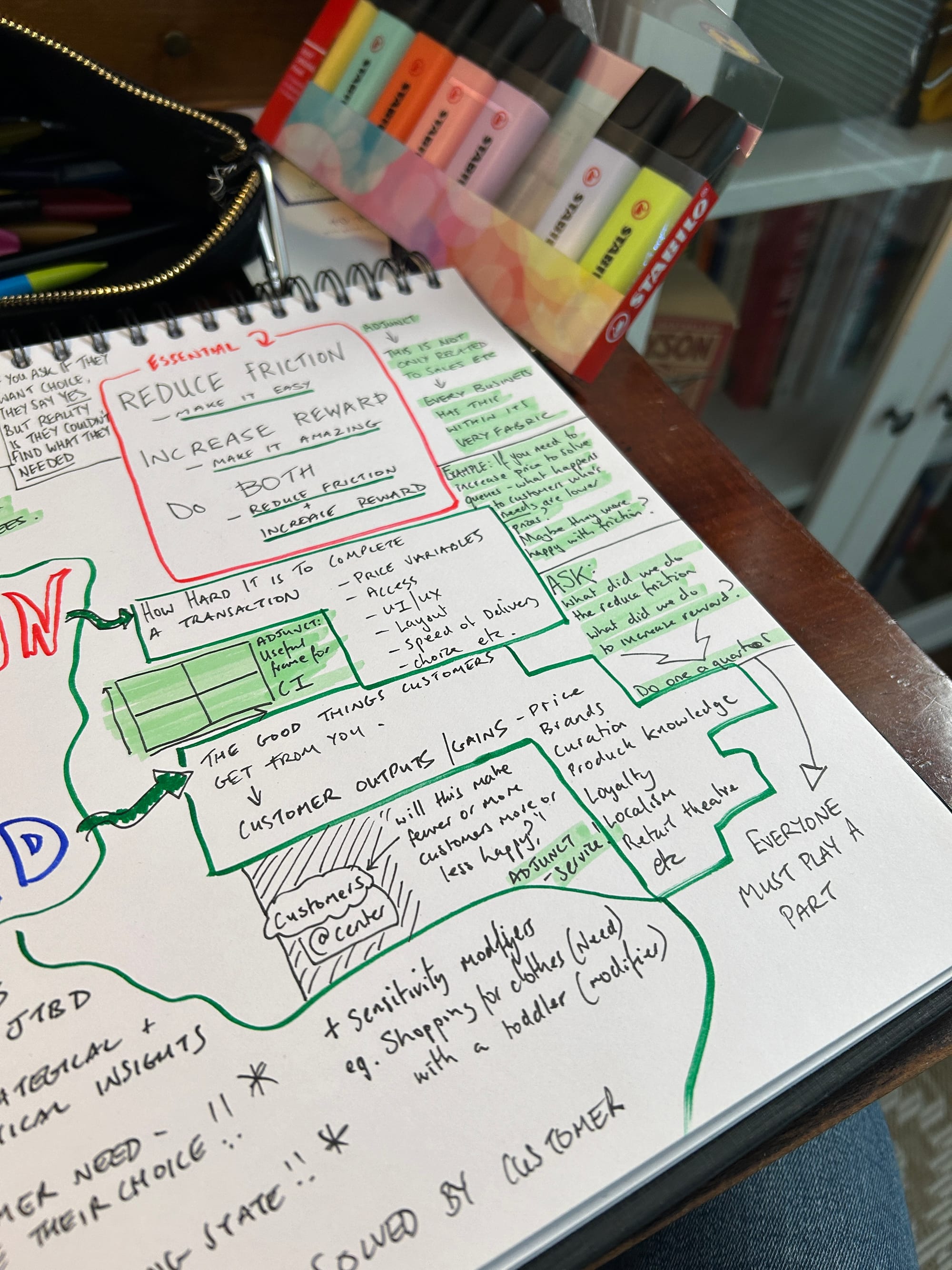

A quadrant you can feel

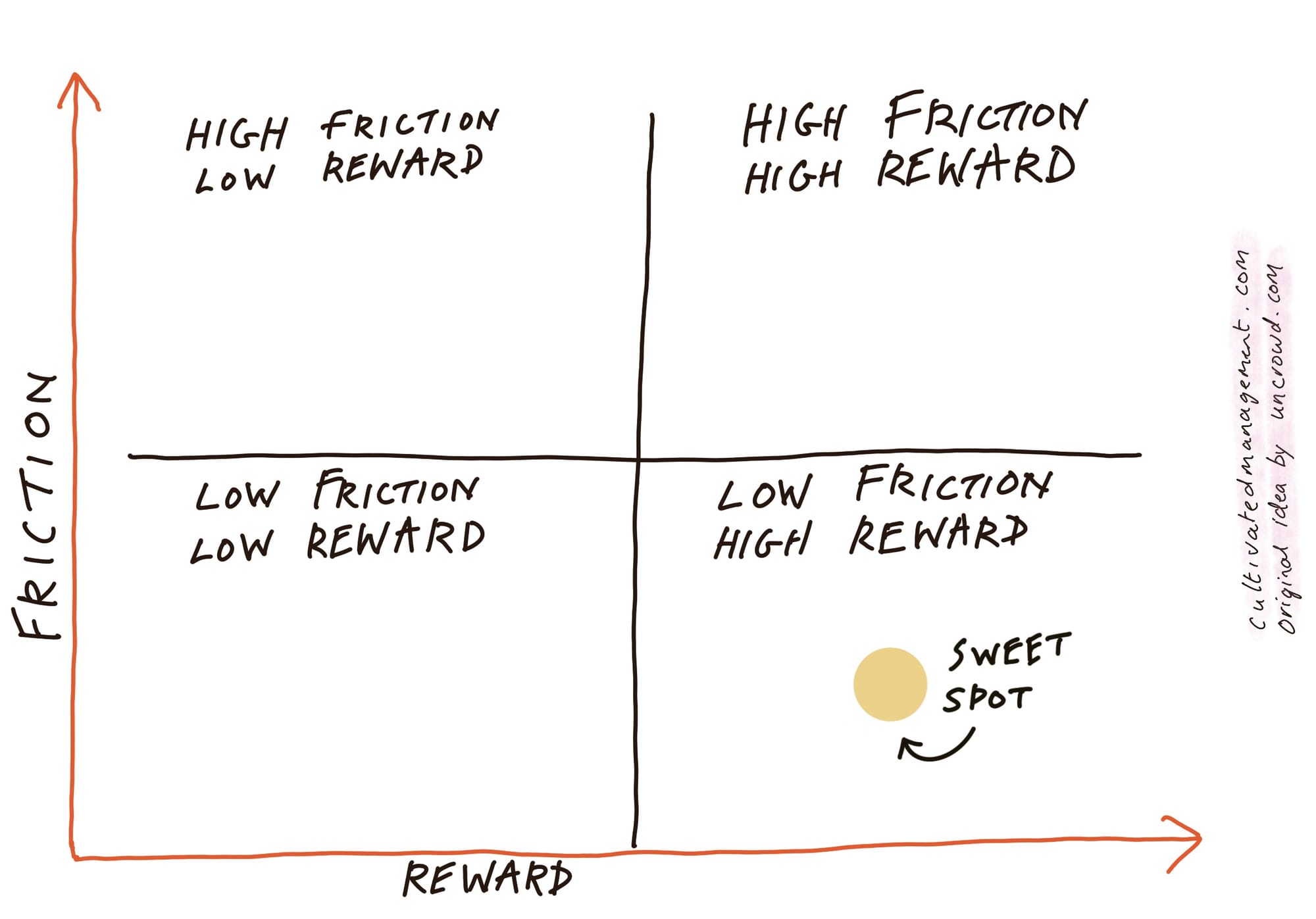

Friction and reward can be drawn as a simple quadrant.

Low to high friction.

Low to high reward.

But it’s more useful than it sounds, because it’s descriptive.

It names the lived experience of work.

High friction, low reward is where things rot.

Customers abandon baskets.

Employees shrug.

Good intentions turn into fatigue.

High friction, high reward is where people tolerate the effort.

They’ll queue, if the price is right.

They’ll persevere, if the outcome matters.

Low friction, low reward is smooth but forgettable.

And low friction, high reward is the obvious sweet spot.

Not always achievable.

But worth recognising.

What friction really is

Friction is anything that makes good work harder than it needs to be.

The extra step.

The pointless sign-off.

The broken system.

The missing information.

The report written for nobody.

The meeting held because the calendar says so.

It’s also the political friction.

Where truth is risky.

Where clarity has consequences.

Where people learn to talk around reality.

Not all friction is bad.

Some friction protects.

Some friction prevents harm.

Some friction is the cost of being careful.

Some friction keeps the business operating.

The problem is the unexamined friction.

The friction nobody owns.

The friction that becomes “just how it is here”.

Reward is not just pay

Reward is what makes the effort feel worth it.

In retail that’s obvious: price, speed, convenience, reliability.

In work it’s subtler.

Reward can be progress you can see.

Autonomy you can feel.

Mastery you’re allowed to build.

Purpose that isn’t a poster.

Fairness that shows up in decisions.

Belonging that isn’t conditional.

When reward is real, people tolerate some friction.

When reward is thin, even small frictions become unbearable.

A slightly clumsy process becomes a daily insult.

Context changes everything

One of the most useful parts of Hammond’s thinking is the role of context.

Need states.

And modifiers.

What someone is trying to do.

And what is changing the urgency, the tolerance, the emotional weather.

A customer browsing is not the same as a customer panicking.

An employee exploring an idea is not the same as an employee trying to unblock a failing launch at 4:45pm.

The same friction can be tolerable in one moment — and explosive in another.

This is how organisations solve the wrong problem.

They design for an ideal day.

Then act surprised when reality arrives.

Three brief examples

Recruitment is a friction and reward machine.

A slow process with vague communication creates friction that candidates feel immediately.

The “reward” on the other side has to be strong — role, team, growth, meaning — or the best people simply exit.

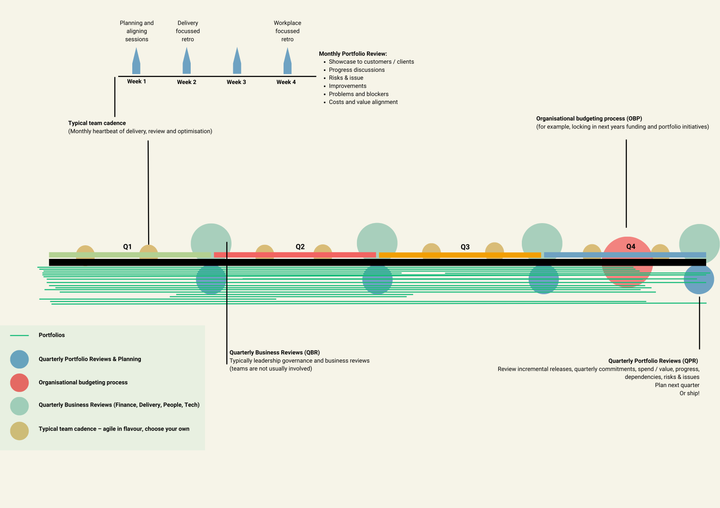

Software delivery often fails for the same reason.

When releases are painful, reward is delayed.

The work becomes heavier than the outcome.

Friction rises.

The system slows.

And customer support is where friction becomes visible.

Not in a diagram.

In a human voice.

When a customer has to repeat themselves five times, friction is the experience.

When a team is punished for surfacing reality, friction becomes culture.

Why leaders should care

Friction is rarely accidental for long.

It’s created by choices.

Policies.

Structures.

Incentives.

Reporting habits.

Approval chains.

Often made with good intent.

Often left unedited.

Leaders also control the conditions that make reward credible.

What gets recognised.

What gets protected.

What gets resourced.

A business can survive a lot of friction if the reward is honest.

But in a world where customers can switch — and employees can leave — high friction with low reward becomes a slow exit.

People don’t always protest.

They just stop.

Friction and reward is not a motivational idea.

It’s a lens.

A way to look at work as it is, rather than as it is described.

And when that lens is used carefully, it does something quietly powerful:

It makes improvement practical again.

Not mystical.

Just human.

Just real.

Learning Notes

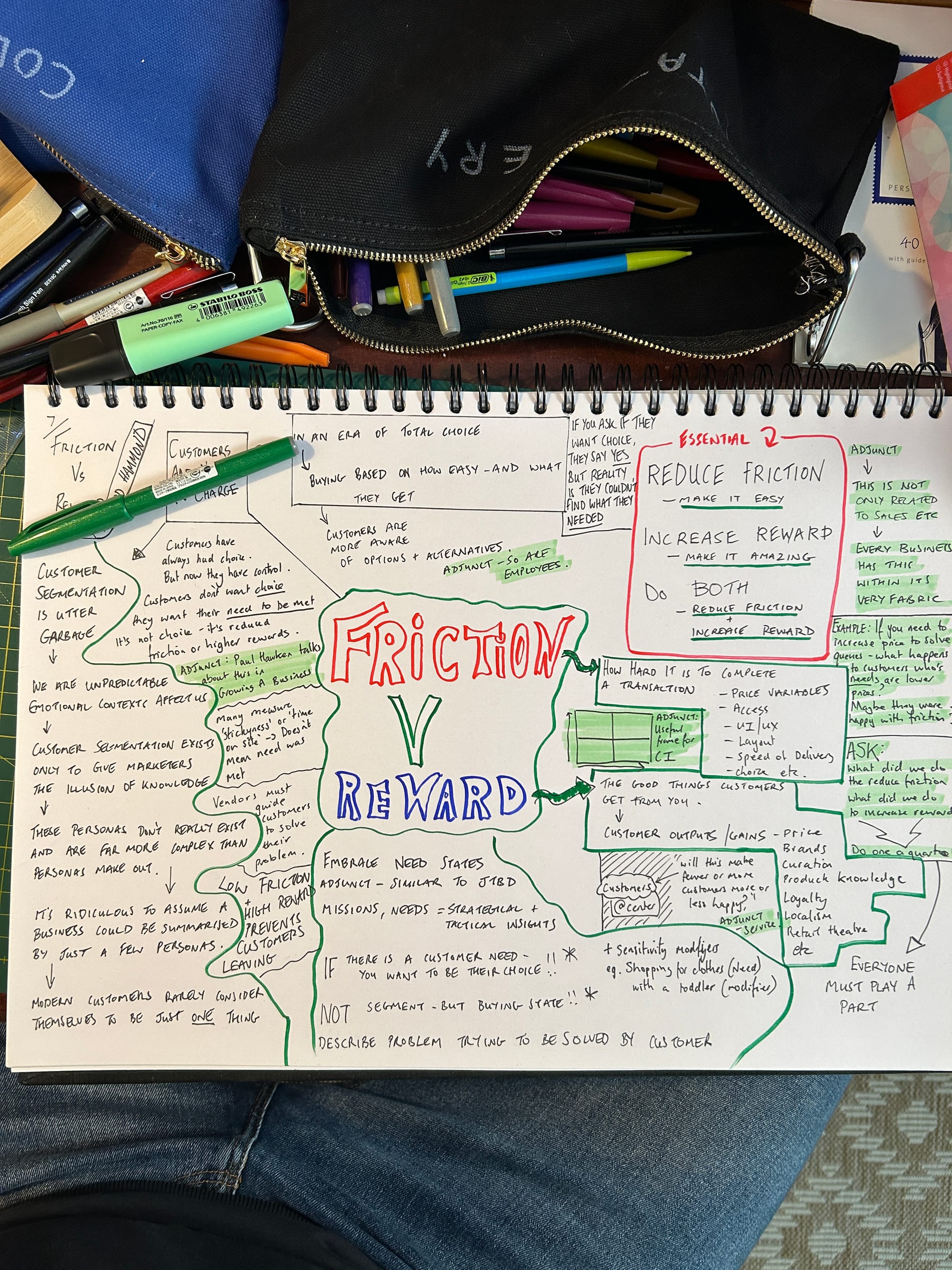

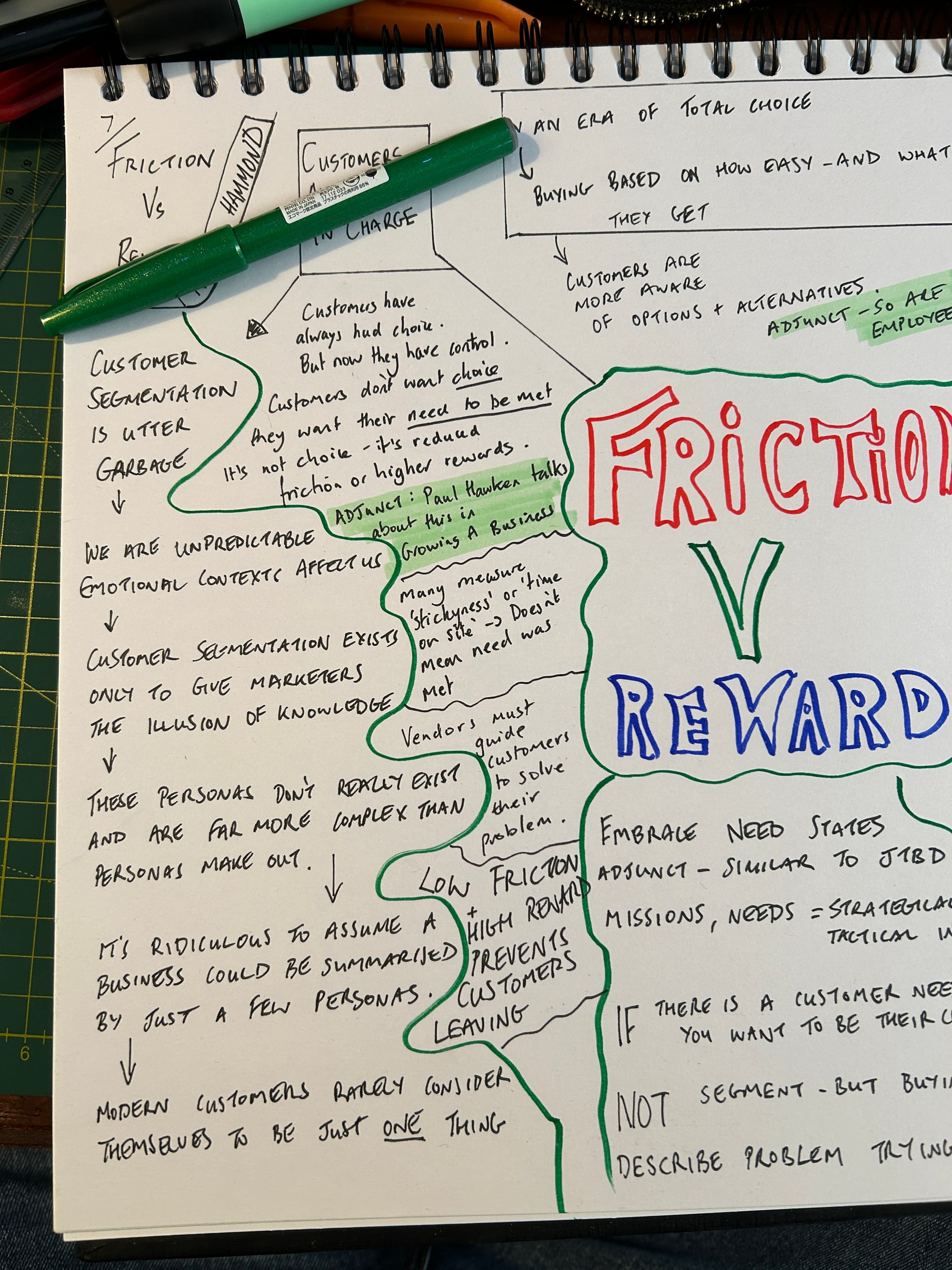

These are "learning notes" - real notes created for personal learning using the 4 step Personal Knowledge Management System of capture, curate, crunch and contribute. What you see here is part of step 4 - contribution.

A gallery of learning notes from the book Friction/Reward by Richard Hammond

This piece forms part of Cultivated’s wider body of work on how ideas become valuable, and how better work is built.

To explore further:

→ Library — a curated collection of long-form essays

→ Ideas — developing thoughts and shorter writing

→ Learn — practical guides and tools from across the work

→ Work with us — thoughtful partnership for teams and organisations